Pad the Shoulder

I was talking with one of our athlete’s fathers the other day discussing his son’s health and performance. We were talking about the usual weight gain for adolescent athletes and then began talking about shoulder health. In talking we stumbled onto a term or phrase that I have heard before and admit to using when I was younger. Tying into our weight gain conversation, “padding the shoulder” came up. Paraphrasing “we want to pad his shoulder in order to avoid injury.” Like I mentioned, I remember using that term in high school and its still out there today.

What does “pad the shoulder” mean?

The definition that you would hear from most people would be along the lines of: to add weight or muscle around your shoulder so that it’s able to withstand more stress placed upon it during play. Or adding muscle around the shoulder so it can act like a cushion in helping take the beating from pitching and throwing.

My translation of that definition would be to increase the size of your deltoid muscle and muscles in close proximity in an effort to almost encase the shoulder joint to keep it safe.

Now lets clarify and debunk this statement. Injuries that occur at the shoulder, rotator cuff injuries, impingement, or labral tears, happen within the glenohumeral joint (shoulder) or result from dysfunction at the joint. That means that we could lock our shoulders in a bulletproof safe, yet that does nothing for keeping your shoulder joint healthy. The term padding the shoulder with muscle and weight around the joint doesn’t do anything for us when referring to the muscles you can see – the deltoid. Sure adding strength and muscle can be good, but it carries no merit without addressing mechanics at the glenohumeral joint.

Think of it as if you put layers of steal and concrete around your car so that you could drive as fast as you wanted and if you hit anything you will be fine. Sure the car will be fine, but if you aren’t strapped in, as soon as you hit something, your body is going through the windshield or going flying in any other direction inside that car. The “padding” is the steal and concrete. The person driving the car represents your humeral head and the interior of the car represents the glenoid (shoulder socket) and surrounding tissue structures.

How Your Shoulder Joint Functions

One of the main functions of the rotator cuff that is often overlooked is its ability to keep the humeral head centered inside of the glenoid. When muscles are unbalanced, the humeral head at rest can be out of alignment. Which is going to lead to some issues.

All over our body at different joints we present with what are called force couples. A force couple is the relationship between 2 or more muscles acting on the same joint. Your muscles each have actions and lines of pull. A muscles line of pull refers to the direction of its fibers and how it exerts force on its attachment site. A muscle action is the movement, function or how it stabilizes a surrounding joint.

Sticking with the shoulder joint, surrounding muscles have jobs to pull in one direction while other muscles at the same joint are meant to pull in an opposite direction. When certain force couples are unbalanced, where one muscle isn’t contributing the right amount of pull, we again start to have issues. The shoulder becomes so complicated because the scapula has 17 different muscles that attach there. All 17 have their jobs to pull on the scapula in different directions.

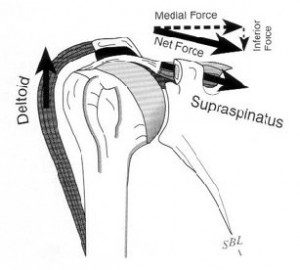

Lets look at one force couple, the rotator cuff and deltoid. Remember, the deltoid is our “pad” in our example phrase. One of the actions of the deltoid is to flex the humerus, or lift your arm over your head. We can say that the deltoid works to elevate the humerus. One of the actions of the 4 rotator cuff muscles works to depress the humerus. The deltoid is a much bigger and stronger muscle than the rotator cuff muscles. With a weak rotator cuff, the deltoid can easily win this force battle and begin to elevate the humeral head too far.

When we have humeral head elevation, we are now talking about an impingement syndrome. You now run the risk of that humeral head rubbing up against your supraspinatus tendon, superior labrum, bursa, and the long head of the biceps tendon. There are quite a few soft tissue, tendons, and bursa that all share space above where you humerus sits to make up your shoulder joint. Having a misaligned humeral head can also play a role in the function of the glenohumeral ligaments, which work to create anterior stability in the joint.

Baseball players and specifically pitchers need a tremendous amount of anterior shoulder stability. Due to the extreme forces present in throwing a baseball, the anterior portion of the shoulder joint is tested. If we put all this “padding” on our shoulder, we would be continuing to feed into this problem of impingement no matter how strong our rotator cuffs are.

The moral of the story is that its not about just adding bulk around your shoulder. It’s about having proper rotator cuff strength and function as well as proper mechanics in sport. Rotator cuff strength is the key.

If we want to pad something to protect the shoulder, do it in the lower body. The lower body is responsible for generating strength and power to your arm. We want our much larger and stronger muscles in our lower body to take the load off of the shoulder. With a weak lower half and core, we put the arm and shoulder on overtime to create all the force needed to throw or hit a baseball. But that’s a whole other topic.

Am I saying not to do any deltoid work? Yes and no.

We do posterior deltoid work with our baseball players at Champion. That’s used in conjuncture with direct rotator cuff work or in an effort to pull certain athletes out a rounded shoulder position. With upper body pressing exercises, the anterior deltoid is firing as well. Dumbbell Y’s and T’s are options but notice how there is no overhead pressing or any other meaty deltoid exercises. We aren’t talking bodybuilding, this is baseball.

This of course is just one example and a look at one aspect of obtaining optimal shoulder health, and working to clarify a misconception that’s still out there.

Keep those cuffs strong and if you are going to “pad” up anything, make it your legs.